By PHIL VERNON

I was speaking last week with James Charlie, chair of the Penelakut Sulxwe’en (Elders Group). James and his siblings were forced as children to attend the residential school on Kuper Island, just north of Salt Spring, now known by its original name Spune’luxutth or Penelakut Island.

James has given testimony numerous times of his experiences at the school, including at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and his brother Raymond (Tony) Charlie has spoken at the Salt Spring library to launch his book, In the Shadow of the Red Brick Building. Today, they continue to advocate for survivors and for increased awareness among the non-Indigenous public about the horrors experienced by children at the Kuper Island Industrial School and at other residential schools across Canada. They also feature in the recent CBC podcast called Kuper Island and in the 1997 film documentary Kuper Island: Return to the Healing Circle.

In 2020, following the revelation by the Tk’emlúps te Secwepemc of 215 suspected unmarked graves at the Kamloops Indian Residential School, the Penelakut Sulxwe’en announced their own work on the issue, where they had already identified over 160 suspected burials near the site used by the since-demolished school in their community.

The Sulxwe’en envisioned a memorial walk through the town of Chemainus to begin the process of healing and reconciliation — for survivors and tribal members as well as for friends and supporters. That first year over 1,500 people poured up the streets of Chemainus, gathering at Waterwheel Park to hear songs, prayers and testimonials from survivors of the school.

In subsequent years the Penelakut Tribe’s search for more graves has continued, resulting in more burials identified at a new site near the grounds of the Kuper Island School, James told me. Evidence found by technicians using ground-penetrating radar and drones indicate an additional 36 “small body” burials, expected to be the babies birthed by girls attending the school who were raped, according to survivor accounts, by the residential school brothers or priests with the collusion of the nuns.

James said that technicians working with the tribe are preparing to use a new type of sonar to scan the sea bed off the shore in an effort to corroborate other survivor testimonies. Tormented by their memories, some who were among the older boys at the school say they were directed by authorities to throw gunny sacks into the ocean from the wharf. Many times they were forced to do this and each sack, they say, contained a baby.

According to the technicians, traces of these remains may still be identifiable using their advanced technologies, despite the passage of time and tide.

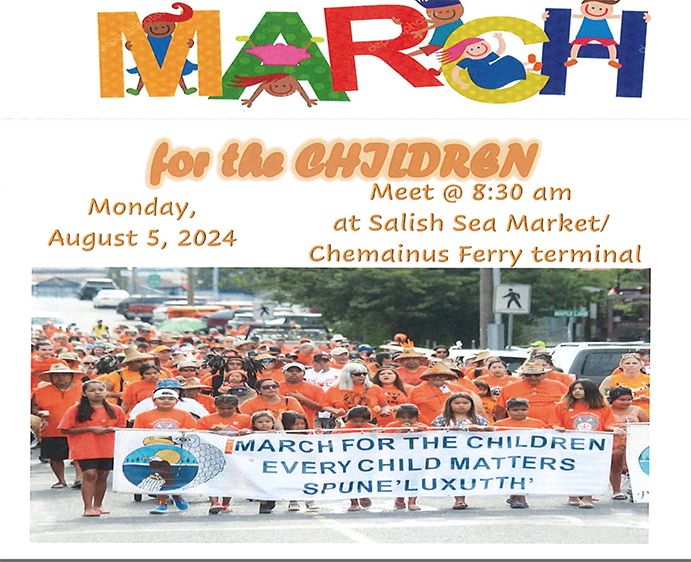

This year, the Penelakut Tribe has invited us back for the Fourth Annual March for the Children, to take place Monday, Aug. 5 in Chemainus — once known as Sunuwnets, the largest Penelakut village before colonial authorities burned the longhouses and drove the families away. Supporters are asked to gather at 8:30 a.m. at the Salish Sea Market next to the ferry terminal, then the procession will wind up the hill to Waterwheel Park.

The Penelakut feel so supported by Salt Spring, and islanders are encouraged to attend. If you need a ride, or have room in your car for another, please email pcvernon@gmail.com or chrismarshall2406@gmail.com with “car pool” in the subject line.