A project launched this summer on Salt Spring hopes to build resilience to emergencies through one of the island’s greatest strengths: local food production.

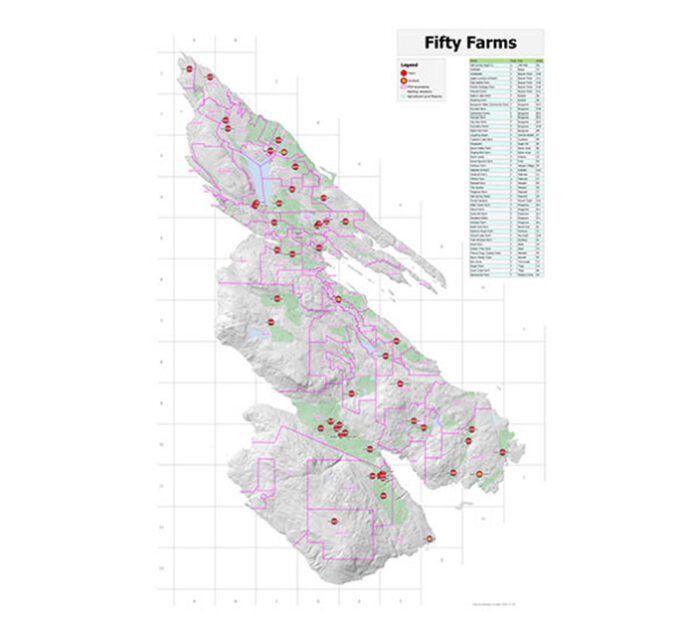

Salt Spring’s rich and diverse food production capability is the foundation upon which the broader emergency food sovereignty goals driving the new Neighbours Feeding Neighbours (NFN) initiative are built, according to co-coordinators Grace Wampold and Heather Picotte. The effort, partly funded by a grant from B.C.’s Investment Agriculture Foundation held by the Salt Spring Island Farmland Trust, means to flesh out an understanding of how Salt Spring’s food resources could be leveraged in an emergency, geographically organized — at least for now — through the extant Salt Spring Island Emergency Program neighbourhood pod system that covers the entire island.

“The idea is that we connect people with the farms and other food producers in their neighbourhoods, help build relationships between them,” said Picotte. “Then when we have an emergency, those relationships will be in place.”

The notion was built out from discussions during last November’s Food Summit; in addition to developing a broad inventory of what food Salt Spring’s growers grow, NFN is keen on looking at infrastructure. That includes storage — water and food storage, keeping things cold — and alternative ways of making things work if the power goes out.

The effort is structured so far around farms that already lie in individual neighbourhood pods. Picotte said the first iteration would focus on identifying 10 pods where food was produced, and organize gatherings so people could get to know their food producers. It’s a “living list,” said Wampold, for sharing with neighbours –– think potlucks and other face-to-face gatherings, building community and imagining ways they can work collectively in a crisis to increase capacity.

“Not all farms have the same resources,” said Picotte. “They can’t all be expected to go from a CSA box program with 50 boxes to like 100 instantaneously when there’s an emergency, it’s impossible. So we need to meet people where they are and see what they have to offer.”

Salt Spring is a broadly agricultural island, observed Wampold. In addition to the relatively large number of crop farms, there are homesteads and people who simply grow food in their backyards; there are hunters and those who understand the resources of the island’s food forests. There are also many who keep livestock –– an asset that needs to be protected in any emergency.

“A lot of homeowners who live on a rural property might have a few goats, a few sheep, cows, ducks,” said Wampold. “Maybe they keep bees. Part of this is connecting with those people so that they have a plan for evacuation.”

Farms, said Wampold, have traditionally served multiple purposes in communities, being not just food producers but gathering spaces.

“That makes them great muster points in an emergency,” said Wampold. “And they often have resources like water that are less common for people who are just kind of doing it on their own, living more remote.”

Picotte said the duo had toured six farms already to talk about planning, and one question kept cropping up.

“They would ask, well, what kind of emergency are you planning for?” said Picotte. “I mean, that’s it; it could be anything.”

Top-of-mind threats always include fire, she said, and basic supply chain disruptions — imagine a flood that might cut off a highway, or longer storms that disrupt ferry service. Picotte said NFN had consulted with emergency services manager John Wakefield, who laid out the idea behind the “unforeseen emergency of two weeks’ duration” as a starting point.

For those who might not get around that well in an emergency — whether anticipating a physical challenge like day-to-day difficulties with walking, or a geographical one like living at the end of a remote road that could be blocked by trees — there’s an added urgency to planning ahead.

“Most people have two or three days’ worth of food in their house already,” said Wampold. “Once it creeps into two weeks, that’s when you are starting to finish everything in your freezer and probably knocking on your neighbours’ doors.”

And apart from those sudden upheavals that disrupt our lives in an instant, emergency preparation can also build capacity to adapt to the more gradual changes or chronic stresses we experience.

“These sort of slow-moving emergencies that we’re seeing,” said Picotte, “certainly climate change, but also in terms of food and fuel costs rising, or land and housing becoming more expensive.”

Food sovereignty is a naturally attractive concept for many independently minded islanders, Wampold said; but emergency food sovereignty, like most emergency planning, is most effective when approached as a group exercise. It’s a bit of a contradiction, she admitted, but for a community already well-steeped in food exchange and bartering, where relationships — particularly since emerging from the acute stage of the pandemic — are so valued, Neighbours Feeding Neighbours is confident the whole can be greater than the sum of its parts.

“We have a lot of sovereign individuals,” said Wampold. “Our hope is that communities can help each other be sovereign.”

Residents are encouraged to take NFN’s emergency food questionnaire online at nfnsaltspring.org — with answers held in strict confidence, and data aggregated anonymously — as well as reach out to join or help plan pod events like farm tours and potlucks.